Remember that the sonnet is originally Italian, and the early sonneteers mainly just copied the Italian sonnet form. No only did Shakespeare introduce a new rhyme sequence to the sonnet form but also a new rhythm. Rhythm: Shakespeare gives us blank verse! (I should point out here that sometimes Shakespeare did break this convention to present the volta in the couplet of the sonnet, such as in Sonnet 130, “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun”.) The “this” that Shakespeare is referring to is the sonnet we just read.

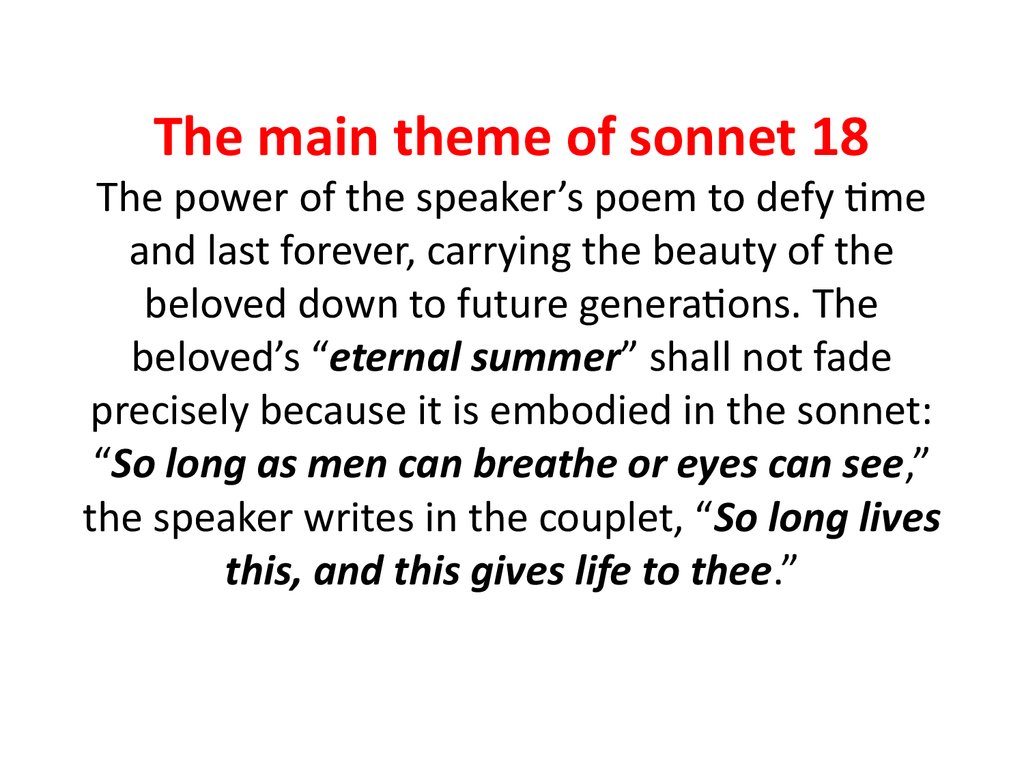

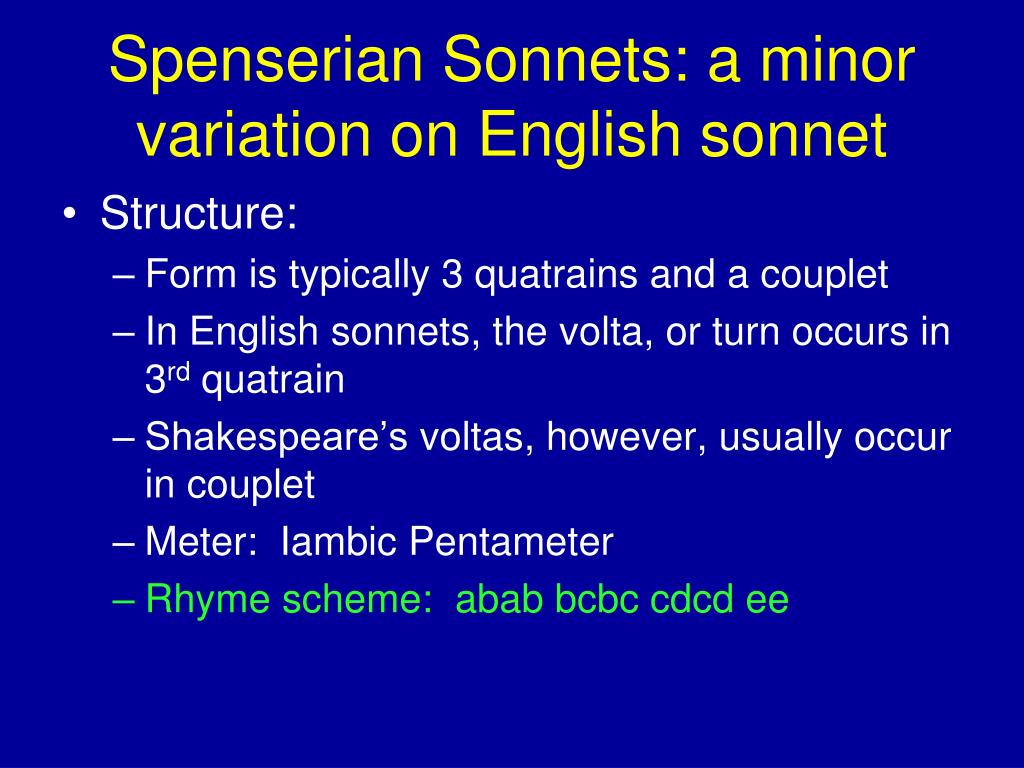

Consider line 9 in Sonnet 18: “But thy eternal summer shall not fade.” Shakespeare presents a way for the young man to preserve his beauty for generations to come, and it is through poetry: “So long as men can breathe and eyes can see,/ So long live this and this give life to thee” (lns 13-14). The volta is the point when the sonneteer offers a response to the first eight lines. How then will the beauty of this young man escape diminishing over time? In line 9, Shakespeare begins to give us the answer – it here that Shakespeare presents the volta, or turn. Take a look back at Sonnet 18: in praising the beauty of the youth male (yes, Shakespeare wrote this sonnet to a young man), Shakespeare points out how all physical forms of beauty fade – a summer’s day has “too short a lease,” a May flower is subjected to harsh winds, and the Sun’s rays are often dimmed by clouds. Generally, the first eight lines of a sonnet will develop some crisis or problem that the poet faces. Line 9 in sonnet is a very important line. Instead of the Petrarchan sonnet of a octave followed by a sestet, Shakespeare gives us three quatrains, four lines of verse grouped together by a rhyme sequence, and a concluding couplet. Shakespeare published his sonnets in 1609 This rhyme scheme, an octave followed by a sestet, predominated the sonnet tradition until Shakespeare, who really went against the grain by introducing a new rhyme scheme for the sonnet: abab cdcd efef gg. Here’s what this rhyme scheme looks like divided in Shakespeare’s most famous sonnet, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” (Sonnet 18): The first eight lines are known as an octave and the following six lines, a sestet. (Refer to the English translation of “Upon the breeze she spread her golden hair” on pg 1090.) Petrarch divided the sonnet into two stanzas – groups of verse that are connected together through a repeating rhyme sequence. The Italian, or the Petrarchan, sonnet rhyme scheme goes abbaabba cdecde. The first convention, or rule, of sonnet is that it consists of fourteen lines – this is why the sonnet is sometimes called a “fourteen liner”. You might find it helpful to make a list of them for yourself. I am going to use quite a few literary terms when writing about the sonnet. The way to understand the sonnet is by separating it into two parts: form (rhyme and rhythm) and content (what is it about). (Hence why a Shakespearean sonnet is also known as a English sonnet.) For the past nine hundred, the sonnet has become the most recognizable form of poem. However, Shakespeare revitalizes the sonnet form, making it uniquely English. By the time (he writes them around 1593 and publishes them in1609) Shakespeare writes his sonnets, of which there are 154, the sonnet tradition was waning. In England during the 16th century, the sonnet became the most popular form of poem to write, Poets, such as Sir Phillip Sydney, Edmund Spenser, Lady Mary Wroth, wrote long sonnet sequences that would often tell the story of an unrequited lover’s desperate pleas to the object of their affections. Their work in the sonnet form inspired that of early English sonneteers, Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard who are considered to have written the first English sonnets. However, the Italian Renaissance poets Dante and Petrarch were the ones who really popularized this poetic form. The sonnet originated in Italy during the 12th century. So this week we are the beginning of our exploration of the sonnet, considered to be the workhorse of love poetry.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)